Michael Sedano

The vision on the page blinded me to the world around me and my own memories. The forgotten farmworker shack sealed against time, a dusty lump on the floor perhaps an abandoned boot, then realizing a desiccated cat that waited patiently until no one came to open the door.

Who is this poet I’ve just met, Rigoberto González, who stuns me like this? The years since 1999’s So Often the Pitcher Goes to Water Until it Breaks have filled in a partial portrait of a complete artist: poet, college professor, critic, novelist, painter, memoirist.

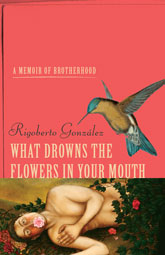

The pen of memoirist González brings his difficult familia to public scrutiny, in his 2018, What Drowns the Flowers in Your Mouth: A Memoir of Brotherhood.

The memoir extends Gonzalez’ reporting on intimate familia, personal, emotional matters. That the book jumps into dark matter is a product of truth, and a deliberate style.

González speaks to his hard-edged reporting in a 2007 interview (link), when the writer told La Bloga’s Daniel Olivas,

if I was going to write about my life I was going to offer it to the reader completely, not selectively, and that meant including the ugly parts too. I come from a home where humor and storytelling were the everyday expressions of love, but so too where violence and abuse were expressions of frustration and hardship.

What Drowns the Flowers in Your Mouth is published as part of University of Wisconsin’s Living Out Gay and Lesbian Autobiographies series. A four-page listing of titles appended to this volume attests to the market for targeting specific readerships.

More readers will find this interesting work where booksellers stock it among the general titles, as well as LGBTQ shelves. The audience of this book is anyone pursuing exemplars of the memoir genre. Being that memoir is the fastest-growing genre among an aging population, anyone who wants to write a memoir needs to read What Drowns the Flowers in Your Mouth.

Any writer who fears saying certain things about real events and people in their lives needs to read this book for permission.

Writers and poets facing personal hardship need to know what got this poet through it.

“It” is the ugly. Orphanhood, death, abandonment. Big brother Rigoberto is driven by instinctive manda to protect his little brother in a world of abusive abuelos. Their father comes back now and then, infecting the narrative with negativity for a few pages until he’s evicted again. This is their lot and each deals with what comes in his way.

Readers seeking equipment for living in these pages will find two strategies but no consejos. Number one is aguantando.

The father endured a life’s oppressive reality through story. That creative spark is something the author inherited from him, in the home, in the DNA. The author grew up aguantando by thinking, reading, being outspoken when the situation demanded, hiding, withdrawing into other people’s narratives when all he could do was aguantar. Then he got out, strategy two.

Little brother isn’t motivated to pursue an escape despite summers piscando la uva. He takes it. Then he drops out of school, settles into the local ambiente, marries, has kids, gets a gas station job, struggles. Aguantando.

Big brother is big time. World traveler, celebrated, paid to write, his name spoken in important places. The author’s public doesn’t see exhaustion, incessantly writing to-spec to raise cash to support his struggling brother. There’s a lesson of sorts there for every writer: when you need more money, write more and write better.

Sixteen chapters track the González family’s progress from isolated Michoacan to a wilderness settlement outside Mexicali. Side visits to the maternal Alcala family put an exclamation mark on the loveless isolation defining the two boys’ lives.

Reading What Drowns the Flowers In Your Mouth is a literary treat for its substance, detail, expression. The opening page of the penultimate chapter, “The Wondrous Flight of the Hummingbird,” says not quite all with its beautifully woven tapestry of language; poetry, irony, disillusion, sorrow, and finally acceptance.

The name of the town at the northeast shore of Lake Patzcuaro is pure onomatopoeia. Say it- Tzin-tzun-tzun-and a hummingbird zips by with each syllable. These elusive little birds are so fast they're invisible and can never be caged. In fact, the only way the people of Tzintzuntzán can attempt to capture a hummingbird is to carve one out of wood, or to sculpt one in iron. The only way for visitors to own one is to buy it. I brought two of them with me that hang from the kitchen doorway of my NYC apartment. As soon as I put them up, I realized how ridiculous this illusion was since the wings are frozen midflight and the bodies dangle from fishing lines because what I "caught" was nothing less than decorated dead weight. These are memorials to the fleeting hummingbird, a wondrous feathered creature whose population has been dwindling over the years. I saw hundreds of memorials in Tzintzuntzán, but not a single living example of what all that artistry honors. Still, it is difficult to challenge the town's name-it is the place of the hummingbirds. They are everywhere: on furniture, on pottery, and stitched near the hems of pretty little dresses.

The chapter is a valedictory letter to a little brother from big brother. Conspiculously absent here is abuelo, and no talk of their father’s abuse. Turning a blind eye to a father who weaves in and out of their lives always leaving a bad taste puts together two words in the same sentence that would seem unlikely given the history of the man we’ve had to endure, “paternal duty” and “father,” as if there can be redemption for leaving the boys to be lashed and tortured by abuelo’s cruel words and capricious control.

The book's thread about physical disability casts light upon the dark mood infecting the author's account of his boyhood. Forced by MS-like symptoms to walk with a cane, physical incapacity wears on the man’s sense of personhood, as well as denying him physical independence. Where escape had been his life’s praxis he becomes prisoner of his disability, and it’s a hard thing to aguantar.

Illness becomes the lens through which the memoirist constructs his scenes. Where a body feels pain, the mind resides in misery and shuts out the rest. The closing chapters, with their diction of reconciliation, reflect the author's growing strength and healthy prospects for an able-bodied future.

Physical debilitation progressively surrenders to a patient's determined diet and activity, and the right pills. The man sheds weight. Now eroticism grows in awareness and usefulness, he can flirt again. Reinvigorated, the artist rededicates time to being productive and joyful. It works; there is this book.

La Bloga Sponsors Face Your Fears Writers Workshop With Ana Castillo

When La Bloga learned that Ana Castillo was contemplating a west coast swing, Michael Sedano offered to host a Pasadena workshop on behalf of La Bloga. At first, the plan was to recruit a donor to underwrite the entire effort and award scholarships to all participants. That plan got hung up on technical financial details and institutional mordida.

Plan B was to sponsor a no-host workshop at the public library. Demand immediately filled the space, generating Plan C. We added a workshop at Casa Sedano. The author would be kept busy with two workshops the same day and more writers would share the experience.

Writer workshops play vital roles in literary culture. Workgroups who nurture and safely critique one another’s work are indispensable to many writers. Workshopping with a professional author is another essential element in a writer’s growth. Personal insight, Q&A, one-on-one environment, small group interaction offer ineffable benefit to one's skill.

Giving local writers access to Castillo’s workshop was the prime goal of the plan. Better writing would be up to them.

Having fun doing it was an important benefit for the residents of Casa Sedano.

This is the first writer workshop Casa Sedano hosted. We’ve welcomed Mental Menudo, Mental Cocido, Book Releases, Backyard Floricantos, Living Room Floricantos, Guest Author Readings, and now Face Your Fears Workshop for 15 writers congregating around a dining table.

For writers, conducting workshops is an extension of one’s marketing and promotional responsibilities. Preparing the workshop is a demanding job for a travel agent, supply chain manager, promotional factotum, p.r. flack. Local arrangements for lodging and transportation place high priority demands on time budget and purse. Books and other material must ship well in advance against delays. Someone is appointed to receive and store the boxes, then arrange pickup and transfer to the workshop destination. A workshop is a major project involving details worthy of making and following a checklist.

Arranging workshop space entails institutional fees, setup against deadline, parking and transportation issues for participants.

Getting the public room at the Santa Catalina Branch of the Pasadena Public Library became a lesson in civic resources. Six phone calls to the branch, a website message, two calls to the central office, and three visits to the branch, and a check, secured the public room. An assistant city manager sent a query to the central office, a happenstance that didn’t help attitudes at the local branch.

A workshop’s enrollments and attendance are subject to caprice. Last-minute cancellations become headaches. Last-minute adds, disappointments. Even good maps and exact directions don’t get people to the place on time owing to traffic conditions and making the wrong turn someplace. Sometimes garbled information and the vagaries of cut-and-paste email lead to inconvenience.

The pair of Face Your Fears workshops were successful, according to Castillo. One disappointment for La Bloga grows from faulty memory.

Arriving at the end of the first workshop, Sedano neglected to bring his good camera and took a group foto with an iPhone. The foto failed. The second workshop, at Casa Sedano, found the Canon camera in readiness. The group portrait and a few candids capture the spirit of writers workshopping facing their fears.

USC Chicano Centro On the Verge

Michael Sedano

I arrived at USC in 1972 with the time-honored stereotype of the “University of Spoiled Children” whose campus perched at the edge of black and raza Los Angeles, but whose black enrollment consisted mostly in world-class athletes. I was on the G.I. Bill and the only Chicano in my graduate program. Down the hall from the Speech Department in Founders Hall, English grad school student Mary Ann Pacheco was promulgating plans that eventuated in El Centro Chicano.

Pacheco and a cohort had a plan that blossomed spectacularly to USC's lasting benefit: they integrated the campus.

Frank Sifuentes was employed as a recruiter and he brought in 102 first-year, mostly first-generation-college raza kids from East Los, Boyle Heights, and eastward. A building at the main campus entry gained a set of murals and a name, El Centro Chicano. In one fell swoop, raza gained an inescapable presence at USC.

Fast forward to last Friday in the confined corridor that serves as today's El Centro Chicano. Mary Ann Pacheco visited a “Power Pan Dulce.” The small gathering represented a cross-section of classes, frosh to grad school. The meeting mirrored the tardeadas the original centro hosted, serving light dessert instead of free buffet.

Pacheco shared unique stories of private confrontations with powerful Deans, threats to yank financial aid over activism, a university president’s curiosity and support, and the suspicions young raza entertained that the old guy with the camera was FBI or a narc.

Now, diversity renews the “battle of the name” that grudgingly settled on “Chicano” out of a welter of terms like Mexican American or Mexican-American, Spanish or Spanish-American. At USC, there’s a move afoot to change to some other name.

An upcoming “Power Pan Dulce” will discuss the idea, or perhaps a proposal, to change El Centro Chicano's name. There's probably a movida bubbling to surface a new handle. As I bade adios to Billy Vela, the director, I reminded him that just because you discuss a topic doesn’t mean you have to change the name.

USC El Centro Chicano alumni and benefactors may wish to contact Vela via his website (link) to voice an opinion. How do “League of United Latin American USC Students,” LULAUSCS, or, “Cardinal, Gold, and Brown Trojans,” sound?

–x suffix words have gained popularity, Pacheco observes, saying she finds “Chicanx” pretentious. She goes with the flow and switches to the dialect of her setting, tolerating "hispanic" if that is lingua franca to her audience.

The actively retired English professor reminds that the word “Chicano” is not an historical artifact but inheres a strategy of emergence and peoplehood. Read Suarez' El Hoyo, Pacheco recommends, to gain a feel for the term.

USC’s public mind and historical memory have forgotten much, and may be on the verge of abandoning a source of power, acting subversively against themselves.

I urge El Centro Chicano’s gente to keep the name El Centro Chicano, to seek instead ways to renew El Centro's founding energy. Fight on.

|

| Willie Herrón mural adorns the side and front of El Centro Chicano in 1973 at Hoover & Jefferson |

No comments:

Post a Comment